Steve Jobs (2015)

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on October 25, 2015 @ tonymacklin.net.

In the movie Steve Jobs, computer pioneer Steve Jobs is in his own world with his own rules.

Those who know him refer to his "reality distortion field."

Writer Aaron Sorkin is in his own "reality distortion field" - art.

He is not concerned with the actual story of Steve Jobs; he creates a character and story that have their own life - borne of imagination. [Think of the movie Bonnie & Clyde (1967)].

Sorkin creates dialogue that the actual Jobs never spoke. The actual Steve Wozniak says that the climactic scene in the movie between him and Jobs in public never occurred. Also the last scene between Steve and his daughter might be comforting, but it's far from actuality.

Sorkin uses some actual facts - culled from the biography by Walter Isaacson -, but artful distortion is his goal. In distortion, as in Jobs's world, Sorkin seeks to find truth.

Steve Jobs is divided into three parts - each around the launch of a new product: 1984 Apple's Macintosh, 1988 NeXT computer, and 1998 iMac.

The workplace is the scene of encounters - snide, lofty, personal, with Jobs seeking perfection. There also is an emphasis on Steve Jobs's personal life with his former girlfriend Chrisann Brennan (Katherine Waterston), and their daughter Lisa (played in different stages of her life by actresses Makenzie Moss, Ripley Sobo, and Perla Haney-Jardine).

Steve adamantly says that he is not her father. He was adopted and twice was a rejected son, which Sorkin jumps on more than once.

Dualities abound - the computer Lisa - "Local Integrated Software Architecture" and his daughter. One important, the other merely human.

Sorkin treats the personal relationship with soft, sometimes clammy hands.

But at his best, Sorkin's dialogue has his patented spirit and intelligence. As in HBO's The Newsroom, Sorkin is often able to create union of head and heart.

One of the basic themes in Sorkin's work is control and the struggle to possess it. The struggle for control inevitably leads to conflict in Sorkin's work. In A Few Good Men (play 1989 / movie 1992) it was control in the military. A young Jack Nicholson would have made a powerful Steve Jobs.

In The American President (1995), it was control in politics; in Moneyball (2011), it was control in baseball; in The Social Network (2007) it was control in Facebook. And in Steve Jobs it's control in the tech world. And in his own life.

The direction by Danny Boyle is skillful and often enhances the language. In the three parts, cinematographer Alwin H. Kuchler uses different equipment as the technological world evolves and progresses. 16mm, 35mm, and digital. Ah, the digital revolution.

Boyle beautifully uses the music and lyrics of Bob Dylan and the lyrical language of Aaron Sorkin.

Walter Isaacson, who wrote the biography of Jobs, once was editor of Time, and Steve Jobs appeared on the cover of Time eight different times, but in the movie this is reduced to one cover on which he didn't appear.

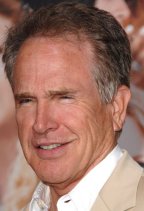

Michael Fassbender gives dimension to Steve Jobs - the tower with tunnel vision. He captures the enigmatic nature of the title character.

Kate Winslet plays Joanna Hoffman, Steve's marketing chief and personal assistant - she even gets him a shirt. Winslet is toned down. She is not arrogant, but makes her character credibly perceptive and supportive.

The young actresses who portray Lisa avoid making her cloying. Boyle deserves credit.

Seth Rogen is almost typecast as Steve Wozniak. It's a relief that Sorkin doesn't succumb to Woz's fervent plea to Steve about the Apple staff, even at the end.

Michael Stuhlberg is adequate as engineer Andy Hertzfeld, but Andy's last encounter with Steve is not one of the film's best scenes.

Jeff Daniels, as always, is fine as Apple CEO John Sculley. Sorkin knows his rhythms.

Katherine Waterston is capable in a thankless role as Chrisann.

Sorkin and Boyle in Steve Jobs have made an arresting "reality distortion field."

Steve Jobs would say, "That's not me."

Sorkin would answer, "No, I've made you more human."

I seldom if ever go back to a theater to see a movie. But Steve Jobs is an exception.

Because of Sorkin's dualities, it demands a second viewing.

At the very beginning we know we're going to witness an intelligent movie. It opens with an actual clip of a television interview with Arthur C. Clarke about the potential for technology in the future. One might remember that Clarke's short story The Sentinel was a source for Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

Steve Jobs is an odyssey.