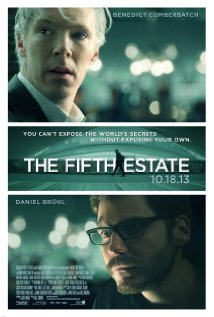

The Fifth Estate (2013)

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on October 19, 2013 @ tonymacklin.net.

The Fifth Estate is a film about audacity made without audacity.

In trying to show the different sides of Julian Assange - the audacious founder of WikiLeaks - it doesn't take a side. It's muddled, uncertain, and sometimes wobbles. It needs commitment.

If one tries to tell the truth, it comes with the conflict between idealism and pragmatism. The truth can hurt, and it may hurt innocent people. The Fifth Estate wavers with that concept. It tries to straddle the truth.

The Fifth Estate ends by paying lip service to seeking the truth, but it throws that out to the audience almost as an afterthought.

The Fifth Estate is the story of how Julian Assange (Benedict Cumberbatch) created WikiLeaks, was joined by Daniel Domscheit-Berg (Daniel Bruhl), and together they created a forum for whistleblowers to reveal corruption in their institutions - banks, governments, and countries.

When Bradley Manning exposes U.S. government secrets on WikiLeaks, the Domsheit hits the fan. He and Assange have a bitter parting, since they have different agendas. Assange refuses to redact the materials no matter what the consequences.

Will truth out? Is it the government's truth or Assange's truth? The film avoids resolving this in any way.

The Fifth Estate is like a news outlet that wants to give equal weight to both sides, even if one carries much more value - moral and otherwise.

If the filmmakers of The Fifth Estate had made All the President's Men (1976), they'd have given equal time and weight to Nixon.

One of the major problems with The Fifth Estate is point of view. One of the film's main sources is the book written by Daniel Domscheit-Berg. It's as if All the President's Men was told by Gerald Ford.

The Fifth Estate has no commitment. Julian Assange and his quest are in the forefront, but Domscheit-Berg and others keep stepping in front of the picture. This blurs and diminishes the sight of Assange.

Other characters get in the way. The subplot of state department official Sarah Shaw (Laura Linney) and her relationship with Libyan informer Tarek Haliseh (Alexander Siddig) is supposed to show a human example, but it seems like leftover footage from Argo (2012).

Another major problem the film has is its soundtrack. The EDM (electronic dance music) is lackluster. The EDM soundtrack worked well for David Fincher in The Social Network (2010) - it won an Oscar for Best Original Score. But in The Fifth Estate the soundtrack is ineffectual. The music tinkles in both romantic scenes, and - except in the scene when it accompanies Assange's visual presentation before an audience - it just wheezes along. The film deserves a better soundtrack.

The writing also is unexceptional. It had at least five writers contributing. TV writer Josh Singer was the main adaptor, but the film seems cobbled together. When the first words spoken in the film are the well-worn, overused quotation by FDR, "The only thing we have to fear is fear itself," we know what's going to follow probably is not going to be unique or subtle. The opening quotation is a sign that the film is going to play it safe.

Director Bill Condon, who captured chemistry so well in Gods and Monsters (1998), isn't able to sustain it here. But Gods and Monsters had his vision, since he wrote it.

By far, the best element in The Fifth Estate is the smashing performance by Benedict Cumberbatch as the chameleonic Julian Assange. With sly looks and elusive personality, Cumberbatch captures the "mad puppet." Assange is intriguing and boorish; driven and reckless; idealistic and deceitful; singular and cultish.

If only The Fifth Estate had not only been true to his spirit, and had taken risks.