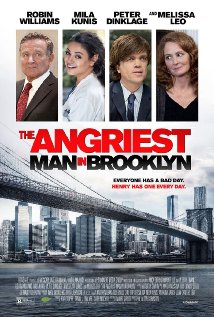

The Angriest Man in Brooklyn (2014)

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on August 16, 2014 @ tonymacklin.net.

It's depressing that Robin Williams' last film released when he was alive is completely lacking wit.

The Angriest Man in Brooklyn is like a brilliant clown stumbling off the stage accompanied by a kazoo. Even the kazoo is out of tune.

The Angriest Man in Brooklyn is an awkward movie with a poor screenplay, trite music, and haphazard direction. Williams tries to keep it on course, but he can't. It flounders.

Misanthropy and rage were not Williams' strengths, but in The Angriest Man in Brooklyn he portrays a raging misanthrope. Williams rants but without vitality. And the flaccid screenplay provides him no opportunity to draw on his creative juices. Henry Altmann, the misanthrope, faces death, but his odyssey is so dour that any "redemption" seems tacked on.

Williams was an actor who could also plumb the dark side of human nature and create palpable characters with demons in them. But in The Angriest Man in Brooklyn the demons are ordinary, dull, and dormant.

The Angriest Man in Brooklyn is about Henry Altmann (Williams) who finds out that he is dying of a brain aneurysm, and then bolts out of a hospital. The substitute doctor Sharon Gill (Mila Kunis), who can't grieve for anything but her cat - it's that kind of movie - tries to find him. He leads her on a bumpy, lumpy chase.

Facing his final moments of life, Henry decides to try to make amends with "family." And Sharon seeks to find the real her.

Any reality they find is only in the shallow minds of the screenwriter and director.

The screenplay credited to Daniel Taplitz is a paltry adaptation of an Israeli movie, and the director Phil Alden Robinson further cheapens it. He bathes everything in constant syrupy music. Robinson once worked with James Earl Jones, and drew on his vast humanity in Field of Dreams (1989). In The Angriest Man in Brooklyn, Robinson demeans Jones with an awful bit about a speech impediment, which Robinson obviously thinks is amusing. He also wastes Louis C.K. in a role that could be played by a broom closet.

Mila Kunis, as the doctor, outshines Williams, and Peter Dinklage is appealing as Henry's brother. Melissa Leo and Hamish Linklater barely survive as Henry's wife and son. Williams is limited to a connect-the-dots-role. He's best off the page, but he never gets a chance to make that move.

Only in one sequence - a scene with a policeman - does Williams deliver dialogue with his usual zeal. And perhaps the only laugh in the film is when Kunis does some kicking. Williams is kickless. He does have one moment of shaky tenderness when he dances. But mostly he frowns and slogs.

The Angriest Man in Brooklyn is steeped in death. The actual suicide of Robin Williams makes it more relevant than it otherwise would be. A discomforting footnote is that both Williams and Phillip Seymour Hoffmann appeared in Patch Adams (1998).

The Angriest Man in Brooklyn has been pounded by reviewers.

It's startling to realize how long Robin Williams at the end of his career went without making a movie equal to his talent. Arguably, it's a dozen years since he starred in a memorable movie. He participated in the two enjoyable Night at the Museum movies (2006 and 2009), but they were supporting roles.

In 2002 Williams did two excellent offbeat movies - One Hour Photo and Insomnia. He gave intriguing performances of dark characters. One Hour Photo was directed by Romanek, who only made three films. And Insomnia was directed by the estimable Christopher Nolan. Both Romanek and Nolan did stellar work on those films.

Directors were crucial to Williams. They sometimes failed him, e.g., novice Patrick Stettner in The Night Listener (2006). And in recent years he worked for several who lacked imagination and creativity.

But during his heyday he was directed by some of the best: Barry Levinson, Good Morning, Vietnam (1987); Mike Nichols, The Birdcage (1995); Terry Gilliam, The Fisher King (1991); Peter Weir, Dead Poets Society (1989); Steven Spielberg, Hook (1991); Penny Marshall, Awakenings (1990); Chris Columbus, Mrs. Doubtfire (1993); Robert Altman, Popeye (1980). He had minor roles in movies directed by Woody Allen, Deconstructing Harry (1997) and Kenneth Branaugh, Hamlet (1996).

Robin played Osric in Hamlet, but he wasn't a minor player. Maybe he was more Hamlet.

Unlike classic comedians such as Jerry Lewis and Charlie Chaplin, Williams did not direct. If he had, he might have accomplished something like Lewis' The Nutty Professor (1963) or the ten films Chaplin directed from The Gold Rush (1925) to the dark, personal Monsieur Verdoux (1947). But Williams never chose that part of artistry.

Like Lewis and Chaplin, Williams at times veered close to cloying sentimentality. He needed a director such as Mike Nichols, who gave him the discipline and creativity that resulted in the exuberant The Birdcage.

There was a fundamental sweetness to Robin Williams. The only time I saw him falter was when in an interview with Barbara Walters, he joked about dying children. He knew he had messed up.

The career of Robin Williams provided us with laughs, sighs, and gasps.

Many of his movies are bursting with inspired performances replete with wit and style.

But for me the signature Robin Williams antic is not in a movie. But it represents many that were.

If you want to smile or chuckle out loud, just think of Robin Williams doing his rendition of Elmer Fudd doing Springsteen.

Robin is "like fiwre."

That's the way I want to remember him.