Baby, Take a Bow: That's Million Dollar Baby (2004)

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on February 1, 2005 @ Bright Lights Film Journal.

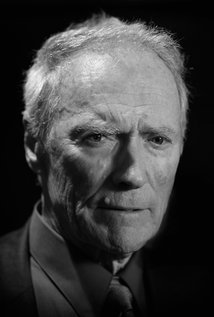

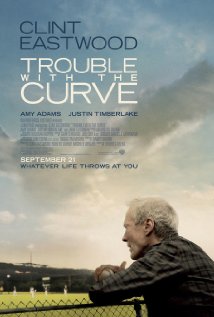

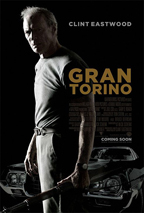

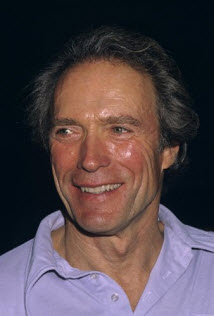

Clint Eastwood continues to surprise and thrill

Million Dollar Baby adds to Clint Eastwood's legacy in ways we might not have expected. It explores emotional terrain as he hasn't done before, and it gives him a kind of role that he has never had before.

We shouldn't be surprised. In the last dozen years, Eastwood has directed as diverse a group of pictures as anyone in movies: Unforgiven (1992) — the gritty, elegiac western; A Perfect World (1993) — the Texas parable; The Bridges of Madison County (1995) — which Eastwood and Meryl Streep drained of most of its pulp; Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1997) — the gay-oriented character study; Absolute Power (1997) and True Crime (1999) — two staple crime dramas; Space Cowboys (2000) — the pop geriatrics adventure; Blood Work (2002) — the last of Eastwood's action parts; and Mystic River (2004) — the moody and provocative mystery.

And now Million Dollar Baby — moody, provocative, and more. Million Dollar Baby is the tale of a wounded trinity: Maggie Fitzgerald (Hilary Swank), Frankie Dunn (Eastwood), and Scrap (Morgan Freeman). Maggie comes to Los Angeles, leaving her trailer trash family in the Ozarks, fervent in her pursuit of an unusual dream, which is to become a professional boxer. She is anxiously committed to getting veteran Frankie Dunn to train and manage her, but Frankie has no interest — he totally dismisses her, scoffing at the idea of female boxing.

Frankie has his own demons. He is completely estranged from his daughter, and he also feels endless guilt for once letting his friend Scrap continue in a brutal fight which cost him one eye. Scrap now helps Frankie run his gym — Scrap's only world — where he has to handle young, undisciplined street kids.

Finally, after her constant cajoling and Scrap's input, Frankie succumbs and reluctantly agrees to train Maggie. A relationship develops between them that becomes like father and daughter, and Frankie — who has given up taking chances — starts taking risks professionally and emotionally. It leads to triumph and a fateful dilemma for Frankie that ends in tragedy — uplifting but devastating.

Eastwood says, "The dilemma of finally reaching some revival in his life, and then having to lose it is a tragic situation. It's a tragedy that could have been written by the Greeks or Shakespeare."

Eastwood as tragedian is an unlikely title. But it fits the 74 year old.

Like Eastwood's best movies, Million Dollar Baby has a strong script. Paul Haggis adapted it essentially from a story in Rope Burns, a collection of short fiction by F. X. Toole (the pen name for the late cut man Jerry Boyd).

Eastwood employs a veteran crew, many of whom have been with him for 25 years or more. Editor Joel Cox first worked with Eastwood on The Outlaw Josey Wales (1975). Cinematographer Tom Stern, who paints with light in Million Dollar Baby, was a gaffer for Honkytonk Man (1982), and Production Designer 89-year-old Henry Bumstead first worked with Eastwood on Joe Kidd (1972). If Bumstead works on Eastwood's next project Flags of Our Fathers, he will be 90.

The age and experience of Eastwood and many of his collaborators give Million Dollar Baby some of its traditional feel. Although it is about a contemporary subject — female boxing — it has an old-time dramatic quality. Much of this is due to the prowess of the three principal actors. The scenes between Eastwood and Freeman are like quiet jazz. Hilary Swank potently adds to the riffs. The trio play off each other to some wonderful effects.

Not so fortunate are some of the lesser players. Least effective is Jay Baruchel as Danger, an inept, mentally-thwarted would-be boxer. It is as though Ken Curtis walked in from the set of a John Ford film. Baruchel is a Canadian with limited acting experience, and this film puts his lack of experience into woeful contrast with the treasure trove of talent around him.

Also at odds with the humanity of Million Dollar Baby is Maggie's family. The audience is supposed to realize how horrible they are while Maggie doesn't, but they are one-dimensional caricatures. We yearn for the scene in the book in which Frankie slugs Maggie's brother and slaps her mother and sister across their faces. This wouldn't fit the tone of Eastwood's movie, but we'd certainly enjoy it.

But one of the best aspects of Eastwood's performance is that he acts his age, where a lesser actor might be tempted to indulge himself. He doesn't chase girls, and he lets Hilary and Morgan do all the fighting. Frankie Dunn is the culmination of Eastwood as actor — he emphasizes that Frankie "is the exact age" he is. It is a brave, restrained performance.

One of the major themes in past Eastwood films is redemption, but Eastwood resists an interpretation of Frankie as redeemed after his climactic act. "I don't know to what degree he's redeemed," says Clint. "He's finally come to the conclusion in his mind that he's granting her last request."

Frankie does what he thinks he has to even though it is off his moral course. (William Munny in Unforgiven may come to mind.) Eastwood leaves Frankie's dilemma open for his audience.

At the end of Million Dollar Baby, Eastwood also counts on his audience. The final image is opaque. "It's in the eyes of the beholder," he says. "Once you finish a film it doesn't belong to you anymore. It belongs to the audience to interpret it the way they feel like interpreting it."

Eastwood continues the point by referring to the ambiguity at the end of Mystic River, when Sean Devine (Kevin Bacon) points his finger like a pistol at Jimmy Markum (Sean Penn). "I go away from the book," he admits. "I don't want to get that exacting. I like it when the audience can play around with it."

Like any self-respecting auteur, Eastwood uses personal touches. His son Kyle composed some of the music for Million Dollar Baby, and Morgan — Eastwood's young daughter with his second wife Dina — has a small scene sitting in a truck at a gas station and sharing a little wave with Maggie. Also, one of Eastwood's production people chose to have Scrap read a Mystic comic book, which makes a piquant connection.

The reviews of Million Dollar Baby have been especially sanguine. They make a positive statement about the film, but even more they are an affirmation of Eastwood. One of the reasons is that at this time of so many banal remakes and artificial movies made from TV shows, reviewers are thankful for an uncompromising effort.

A second reason for the enthusiasm of the reviews is that Million Dollar Baby is like an expected gift. If reviewers didn't close the door on Eastwood's career with Unforgiven , they surely did with Mystic River. What else could he do? But Million Dollar Baby keeps the door open. And most reviewers welcome it and are grateful.

With Million Dollar Baby, Clint Eastwood adds new notes to old music — which is how a master auteur continues to prevail.